When it comes to reading scientific literature, there is the common misconception that it should come as easy as reading anything else. Wrong! Understanding and critically evaluating scientific literature takes years of experience. From my experience, lay people, including science students and early career researchers, often underestimate how hard it is to read an article and tend to misinterpret the findings. Let’s see why!

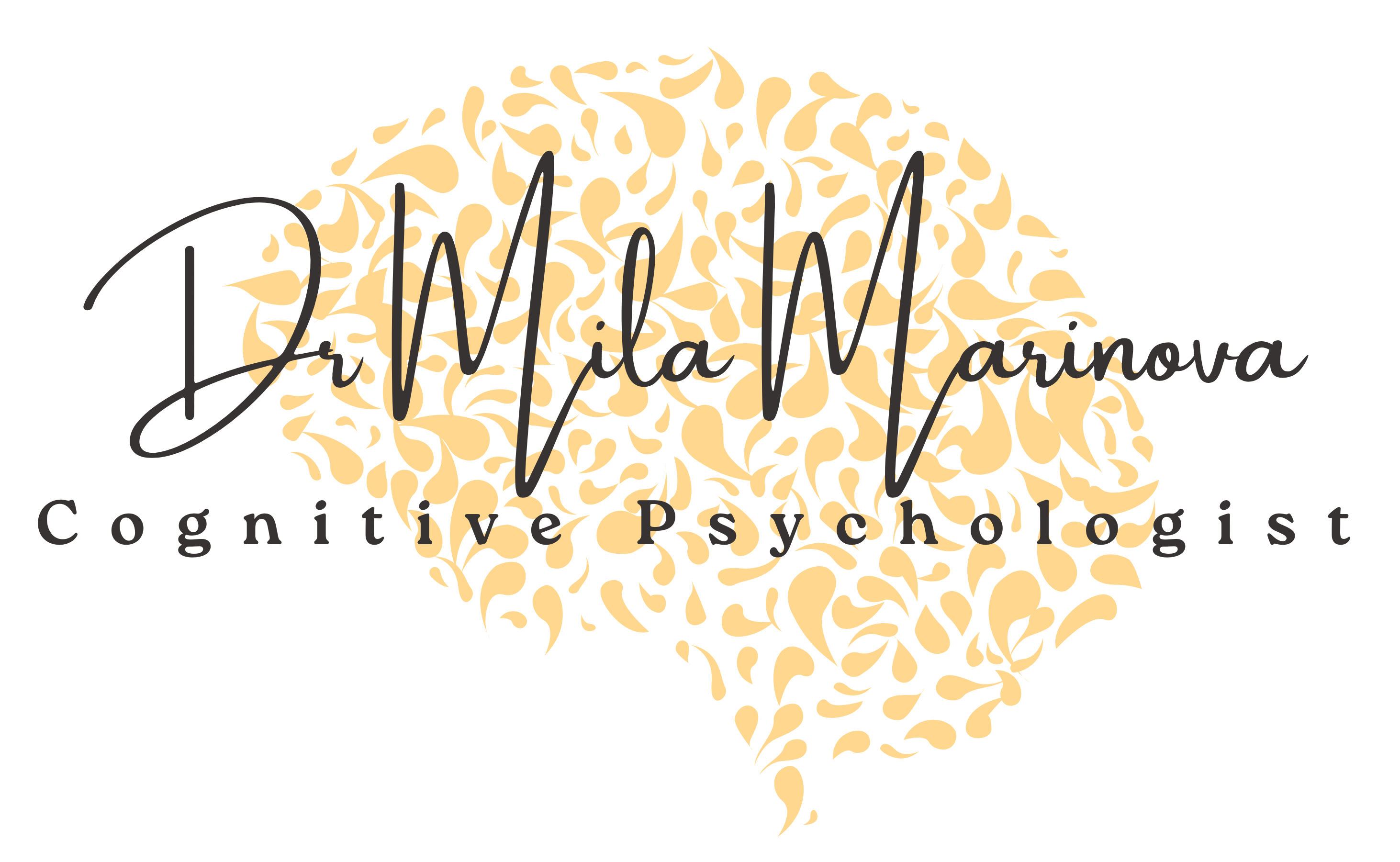

What classifies a scientific article? Scientific articles (peer-reviewed) usually report original research with empirical data. As can you see in the picture below, a well-written article has an hourglass structure.

The section’s width reflects the audience’s breadth: the narrower the part, the more specialized knowledge it requires.

What does each section mean?

The title usually states the central finding or the study’s contribution.

The Abstract is a brief, concise summary (app. 250 words) of the paper.

In the introduction, the authors usually define and clarify the problems they plan to investigate. They inform the reader about the subject by summarising and evaluating studies and theories. This is also the place to identify inconsistencies, gaps, contradictions, and relationships in the literature and acknowledge previous works (results, limits, strengths). Normally, towards the end of the introduction, the author(s) suggest future steps and approaches to solve the issues identified. This is usually followed by stating the research hypothesis explicitly: their assumptions and expected outcomes. A good and ethically conducted research normally states at least two types of hypotheses: an alternative hypothesis (what the researchers expect in case their findings are supported) and a null hypothesis (it usually states the opposite of the alternative hypothesis).

In the methods sections, the researchers describe in detail what they did, how they did it and to whom. This section includes detailed information about what was the population (adults, children, animals, patients) and its descriptives or other particularities (age, sex, profile, etc.), how big the sample was, how it was determined, what were the testing conditions and protocols, experimental manipulations, tools, equipment used, ethical considerations etc. In my opinion (and not only), the methods are the first core part of a scientific paper. This section should usually contain sufficient information presented objectively to enable replication. Based on the methods section, the scientific community determines whether the study is done according to scientific standards and integrity, whether these methods are valid, rigorous, and ethical, and whether they are appropriate for the research question.

In the results section, the statistical analyses and their outcomes are described. Normally, the results section is “dry”: it describes how the data was manipulated and fed to the model or operationalised in the analyses and the concrete outputs (in numbers). The results section is kept free of any interpretation. To me, this is the second core of the articles. Here, in addition to informing ourselves about the output of the study and how it was achieved, we critically evaluate how the analyses were carried out, are they were performed and reported objectively, were the analyses appropriate for the study’s objective, are they complete (maybe some variables should be controlled for) and compliant with the established scientific standards.

In the discussion sections, the authors usually provide a short recap, interpret the findings, emphasise how these findings fit or not with previous studies alongside stating what are the possible reasons for that, what is current study’s contribution to the field, and point out limitations and future research directions. The discussion ends with stating the implications and overall conclusions from the study. When scientists read this part, we also evaluate whether the conclusions are logical and valid: that is, do these conclusions follow from the findings reported in the results section, or were they under/over-interpreted?

The bitter truth is that not everyone can (or should be able to) properly read scientific articles.

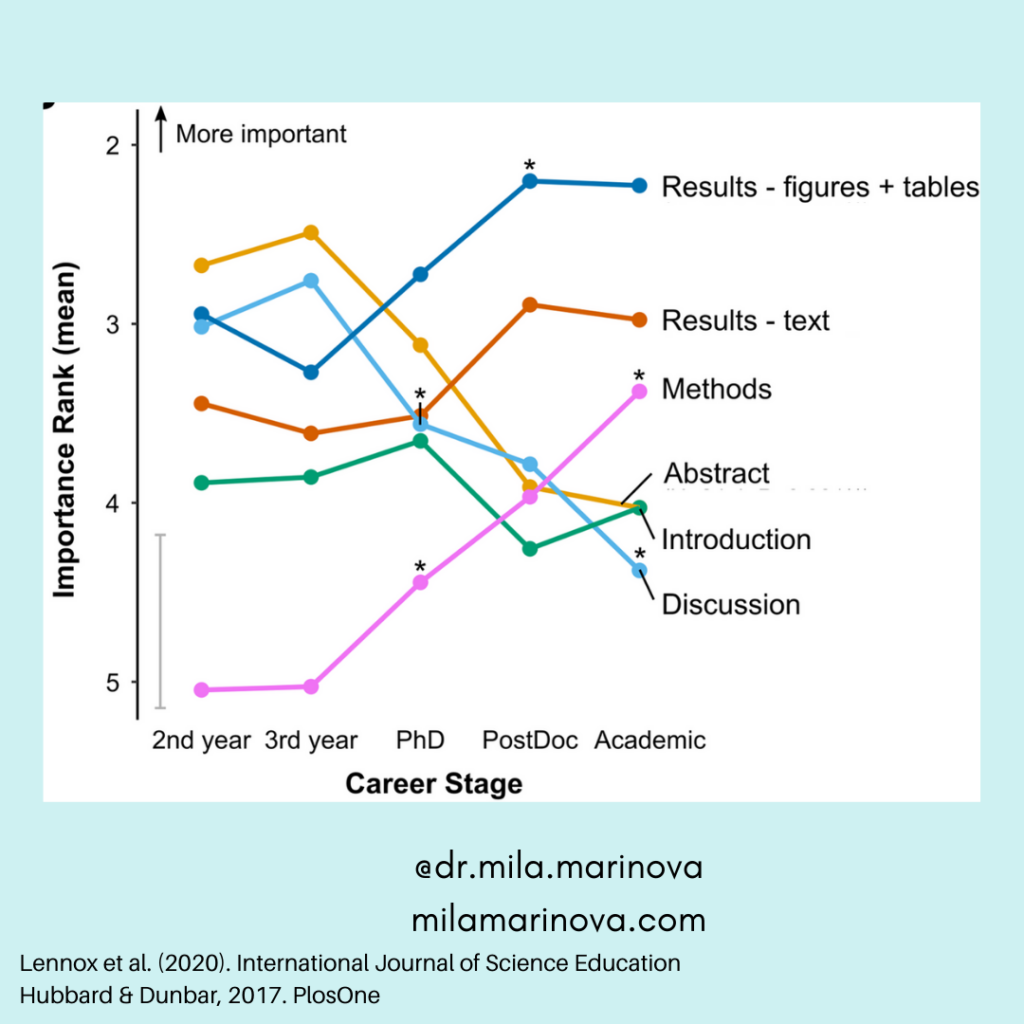

Scientific articles are highly specialised literature. This means they are not readily understandable to lay readers or people lacking sufficient field training. As you can see in the figures below, one of the main challenges in reading and understanding correctly scientific peer-reviewed articles is that understanding the critical parts requires years of expertise. Laypeople and junior scientific trainers struggle to understand and comprehend the important parts of the article.

Inexperienced readers (including university science students) often misjudge what is important in a scientific article and tend to skim-read (right panel). This is due to lack of experience and overconfidence (left panel).

If you still want to read hard-core science articles, here are some tips I give you as a scientist.

Tip Nr 1: If you are a complete amateur or lack any scientific training (in the field), instead of going head-on with science articles, try starting first with a popular science book or popular article on the topic by an expert in the field.

Tip Nr2: If you have or are undergoing scientific training (in the field) but want to improve your reading and understanding skills, try summarizing the research papers you read. Reflecting on the critical parts of the article will help you build a better understanding.

To get started, try these prompt questions:

What is the scope of the paper?

What is the main argument?

What is the methodology? Is it appropriate?

What are the results? Are they logical and valid?

What is the main takeaway message? Does it follow from the results?

What is your (constructive) critique?

Not understanding scientific literature is not an insult to anyone’s intellectual capabilities. Just like not everyone with a driver’s licence can be an F1 pilot, not everyone can or should understand highly specialised literature. This is why having experts and science communicators is important!

.

.

.